- Home ›

- Irish emigration ›

- Irish immigration to America

Irish

immigration to America:

1846 to the early 20th century

Irish immigration to America after 1846 was predominantly

Catholic. The vast majority of those that had arrived previously had been

Protestants or Presbyterians and had quickly assimilated, not least because

English was their first language, and most (but certainly not all) had skills

and perhaps some small savings on which to start to build a new life. Very soon

they had become independent and prosperous. More about pre-1846 immigration here.

Irish immigration to America: The Famine years

The arrival of destitute and desperate Catholics, many of whom spoke only Irish or a smattering of English, played out very differently. Suspicious of the majority Anglo-American-Protestants (a historically-based trait that was reciprocated), and limited by a language barrier, illiteracy and lack of skills, this wave of Irish immigrants sought refuge among their own kind.

The Dunbrody is a replica of an emigrant ship that sailed in the 1850s between New York and New Ross, Co Wexford, (where the replica is moored).

The Dunbrody is a replica of an emigrant ship that sailed in the 1850s between New York and New Ross, Co Wexford, (where the replica is moored).The arrival of destitute and desperate Catholics, many of whom spoke only Irish or a smattering of English, played out very differently.

Suspicious of the majority Anglo-American-Protestants (a historically-based trait that was reciprocated), and limited by a language barrier, illiteracy and lack of skills, this wave of Irish immigrants sought refuge among their own kind.

At this time, when famine was raging in Ireland, Irish immigration to America came from two directions: by transatlantic voyage to the East Coast Ports (primarily Boston and New York) or by land or sea from Canada, then called British North America.

Ireland was also part of Britain, and fares to Canada were cheaper than fares to the USA, especially after 1847. Those that survived the journey often had just one thought on their minds: to be free of British oppression. While many chose to settle in Canada, substantially more managed to find the physical and financial resources to reach America.

The Dunbrody is a replica of an emigrant ship that sailed in the 1850s between New York and New Ross, Co Wexford, (where the replica is moored).

The Dunbrody is a replica of an emigrant ship that sailed in the 1850s between New York and New Ross, Co Wexford, (where the replica is moored).The arrival of destitute and desperate Catholics, many of whom spoke only Irish or a smattering of English, played out very differently.

Suspicious of the majority Anglo-American-Protestants (a historically-based trait that was reciprocated), and limited by a language barrier, illiteracy and lack of skills, this wave of Irish immigrants sought refuge among their own kind.

At this time, when famine was raging in Ireland, Irish immigration to America came from two directions: by transatlantic voyage to the East Coast Ports (primarily Boston and New York) or by land or sea from Canada, then called British North America.

Ireland was also part of Britain, and fares to Canada were cheaper than fares to the USA, especially after 1847.

Those that survived the journey often had just one thought on their minds: to be free of British oppression. While many chose to settle in Canada, substantially more managed to find the physical and financial resources to reach America.

Irish immigration to America - Discrimination

Notwithstanding the lack of trust between the predominantly Protestant America-born middle class and the impoverished Catholic immigrants who arrived in the mid-19th century, the main problem for the Irish immigrant was a lack of skill.

Of course, there were some who were blacksmiths, stonemasons, bootmakers and the like, but the majority had had no formal training in anything.

On passenger manifests the men claimed to be labourers; women said they were domestic servants. In most cases, they had little or no previous experience in these roles; these positions were the limit of their aspirations.

The Boston Pilot

From 1831 to 1920, this national newspaper published 'Missing Friends' advertisements which usually referred to the exact townland of origin of either the person being sought or the person who placed the ad. They route of the individual's journey to America, and even the name of the ship, were often stated.

Many of the ads refer to women, for whom determining the exact place of origin can often be more difficult because they didn't apply for naturalisation (this status was passed to them by their husband).

Some databases charge for this resource but you'll find an incomplete version is available free through the Boston College Irish Studies Program.

A job – a wage – was what they were seeking, and they didn't really care too much about the detail. Being unskilled, uneducated and typically illiterate, they accepted the most menial jobs that other immigrant groups did not want. So-called 'Elegant Society' looked down on them, and so did nearly everyone else!

They were forced to work long hours for minimal pay. Their cheap labour was needed by America's expanding cities for the construction of canals, roads, bridges, railroads and other infrastructure projects, and also found employment in the mining and quarrying industries.

When the economy was strong, Irish immigrants to America were welcomed. But when boom times turned down, as they did in the mid-1850s, social unrest followed and it could be especially difficult for immigrants who were considered to be taking jobs from Americans. Being already low in the pecking order, the Irish suffered great discrimination. 'No Irish Need Apply' was a familiar comment in job advertisements.

The Boston Pilot

From 1831 to 1920, this national newspaper published 'Missing Friends' advertisements which usually referred to the exact townland of origin of either the person being sought or the person who placed the ad. They route of the individual's journey to America, and even the name of the ship, were often stated.

Many of the ads refer to women, for whom determining the exact place of origin can often be more difficult because they didn't apply for naturalisation (this status was passed to them by their husband).

Some databases charge for this resource but you'll find an incomplete version is available free through the Boston College Irish Studies Program.

Irish immigration to America: Steamship competition

After 1855, the tide of Irish immigration to America levelled off. However, the continuing steady numbers encouraged ship builders to construct bigger vessels. Most of them still made the voyage east with commodities to feed England's industrial revolution, but shipowners began to realise the economic advantages of specialising in steerage passengers.

Conditions onboard began to improve -not to a standard that could even remotely be called comfortable today, but improved, all the same.

By 1855 iron steamships of over 1500 tons were becoming increasingly common, and competition was growing. So much so that steerage fares on steamships were often lower than on sailing ships, and voyage time was considerably quicker at less than two weeks.

Quick Links & Related pages

The reduction of voyage time was a two-fold blessing. Not only did this mean the emigrant had to suffer the discomfort of steerage for a shorter period, it also made the concept of Irish immigration to America - the leaving of family and homeland - seem less permanent.

As the size of emigrant ships grew, so it became increasingly common for Irish emigrants to travel to Liverpool, across the Irish Sea in Northwest England, to catch their boat to a new life in America. This huge port could accommodate the larger ships more easily than the small Irish harbours.

Immigration in New York: Castle Garden

New York was the principal entry point to the United States throughout the 19th century and on 3rd August 1855, a Board of Commissioners of Immigration opened the city's first immigrant reception station.

Based at Castle Garden, near the Battery at the southern end of Manhatten, it had earlier been a fort, a cultural centre and a theatre. Now it was pressed into service as a place to receive immigrants.

More than 8 million immigrants of all nationalities passed through Castle Garden before it closed on April 18, 1890. It is now a museum, and also the ticket office for the ferry to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.

Surviving Castle Gardens' records are available on a free online database that also includes a sizeable collection of records dating from 1830 for other ports in America.

The records are mixed together, however, so if you find an entry for one of your ancestors, you will need to verify the port of entry. This can be done either through searching a microfilm of the ship's manifest at NARA or through Ancestry's online collection (fee charged). See below for links for more information.

Where did these Irish immigrants to America settle?

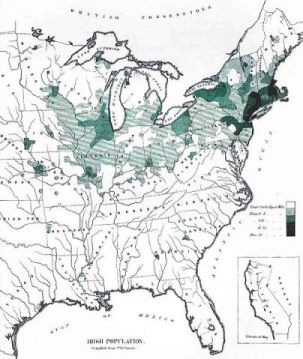

The map below shows the Irish population of the United States based on statistics from the 1890 census.

The data reveals that immigration to New York had been the preference for nearly half a million (483,000) Irish-born settlers. Of these, 190,000 were in New York City.

More than a quarter of a million (260,000) had settled in Massachusetts, chiefly in Boston, while Illinois also had a sizeable population of 124,000 of which 79,000 were in Chicago.

Where did these Irish immigrants to America settle?

The map to the right shows the Irish population of the United States based on statistics from the 1890 census.

The data reveals that immigration to New York had been the preference for nearly half a million (483,000) Irish-born settlers. Of these, 190,000 were in New York City.

More than a quarter of a million (260,000) had settled in Massachusetts, chiefly in Boston, while Illinois also had a sizeable population of 124,000 of which 79,000 were in Chicago.

Irish immigration to America: the turn of the century

After Castle Garden closed in 1890, Irish immigrants to America (and all other immigrants) were processed through a temporary Barge Office. Then, on 1st January 1892, the Ellis Island reception centre opened. Annie Moore, a 15-year-old from Co Cork, was the first passenger processed, and more than 12 million followed her over the next 62 years.

By this time, attitudes towards the Irish had begun to change. The Civil War was probably the turning point; so many thousands of Irish whole-heartedly participated in the war (they made up the majority of no less than 40 Union regiments), and gained a certain respect and acceptance from Americans as a result.

And second or third generation Irish-Americans had moved up the social and managerial ladder from their early labouring work. Some were even entering the professions.

After Castle Garden closed in 1890, Irish immigrants to America (and all other immigrants) were processed through a temporary Barge Office. Then, on 1st January 1892, the Ellis Island reception centre opened. Annie Moore, a 15-year-old from Co Cork, was the first passenger processed, and more than 12 million followed her over the next 62 years.

By this time, attitudes towards the Irish had begun to change. The Civil War was probably the turning point; so many thousands of Irish whole-heartedly participated in the war (they made up the majority of no less than 40 Union regiments), and gained a certain respect and acceptance from Americans as a result. And second or third generation Irish-Americans had moved up the social and managerial ladder from their early labouring work. Some were even entering the professions.

Of course, this was not the lot of the majority. In the 1900 census there were still hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants living in poverty, mostly in urban slums. But economic circumstances were improving for a significant proportion, and the Irish, as a group, were gaining footholds in the workplace, especially in the labour or trade union movement, the police and the fire service.

Their numbers helped. The large Irish populations of cities such as Boston, Chicago and New York were able to get their candidates elected to power, so launching the Irish American political class.

At the turn of the century, Irish born immigrants made up 2.12% of the US population. More importantly, Irish Americans – those Americans born to Irish parents – made up 6.53%. A sizeable group, indeed.

Exclusive to Irish Genealogy Toolkit

- A must-have for Irish researchers