- Home ›

- Irish Emigration ›

- Immigration from Ireland to England

Irish immigration to England

An overview of Irish settlement in England

Where to find genealogy resources

Irish immigration to England dates back further than most people realise. Rather than as a phenomenon of the mid- to late-19th century, the Irish had been migrating across the sea for centuries, usually in search of seasonal work or longer term opportunity.

Liverpool Docks

Liverpool DocksSome towns – especially London, Bristol, Whitehaven – had a sizeable population of middle class Irish traders as early as the 1650s, and, of course, seasonal work, typically agricultural labouring, needed migrants to help with the annual harvests.

See Irish immigration to Britain for the wider picture.

Irish immigration: economic opportunity

In addition to the traditional seasonal movement of agricultural labourers, there were also waves of specialised migrations, when hundreds or thousands of specialist workers responded to skills shortages in England.

The story of Manchester provides a good illustration. Known as Cottonopolis for its links to the cotton industry, it was Britain's industrial heart and its promise of work attracted thousands of poor Irish families from the late 18th century. Even in the 1790s its Irish population was around 5,000.

In the next few decades, many Irish, predominantly from Ulster, were encouraged to transfer their skills to the northwest of England where there was a shortage of native handloom weavers.

Irish immigration to England's counties and towns

Counties with the largest Irish-born populations in 1851:

- Lancashire 8.9%

- Cheshire 5.7%

- Durham 5.4%

- Cumberland 5.1%

Towns with the largest Irish-born populations in 1851:

- London 108,548 (4.6%)

- Liverpool 83,813 (22.3%)

- Manchester 52,504 (13.1%)

Irish immigration to England followed remarkably similar settlement patterns

from 1851 to 1921, despite the overall decline in numbers of people leaving

Ireland for Britain during that period.

Irish immigration to England's counties and towns

Counties with the largest Irish-born populations in 1851:

- Lancashire 8.9%

- Cheshire 5.7%

- Durham 5.4%

- Cumberland 5.1%

Towns with the largest Irish-born populations in 1851:

- London 108,548 (4.6%)

- Liverpool 83,813 (22.3%)

- Manchester 52,504 (13.1%)

Irish immigration to England followed remarkably similar settlement patterns

from 1851 to 1921, despite the overall decline in numbers of people leaving

Ireland for Britain during that period.

By 1832, the town's Catholic population stood at 30,000 and about two out of every three were either Irish-born or of Irish descent.

Just four years later, the number of Catholics had grown to 40,000. Most of this growth was attributed to the Irish community who now made up around a third of the working class population.

The first rumblings of resentment and prejudice date from this time and created what became known as 'the Irish problem'.

Manchester was one of the big three destination cities for Irish immigration to England.

In sheer numbers, London was the largest but it was proportionally small. Liverpool was undoubtedly the most Irish city.

By 1851, more than 18% of its population had been born in Ireland.

Famine refugees in Liverpool

A year after the potato blight first struck in Ireland, Irish immigration to England really took off. Hundreds of thousands of Irish were on the move, desperate for food, shelter and, if they could think that far ahead, a future free of the starvation and poverty that characterised life for the majority in Ireland.

The largest numbers descended on Liverpool. In just five months of 1847, some 300,000 utterly destitute and starving Irish men, women and children arrived in the docks.

This more than doubled the population of the town, which already had a reputation for urban squalor, disease, violence and unemployment.

A 1847 report by Dr William Henry Duncan, the city's first public health officer, estimated that 60,000 people caught typhus and 40,000 contracted dysentery in that one year.

Liverpool could not cope with the vast influx of Irish immigrants; in June 1847, under the new Poor Law Removal Act, about 15,000 Irish were deported back to Ireland.

While many Irish settled in the city, a large proportion subsequently re-emigrated to North America. By 1871, the Irish-born population of Liverpool had fallen to 15.6%, even less than in the pre-Famine years.

Irish immigration to England meant an urban life

While early industrial migrations brought many to the city, not all Irish immigration to England was centred on big urban centres. In Staffordshire, West Cumberland, Co Durham and Northumberland extensive Irish settlements grew up and waned in rhythm with the fortunes of local iron mining and metal manufacturing.

While early industrial migrations brought many to the city, not all Irish immigration to England was centred on big urban centres.

In Staffordshire, West Cumberland, Co Durham and Northumberland extensive Irish settlements grew up and waned in rhythm with the fortunes of local iron mining and metal manufacturing.

A large ironworks in the Northumberland town of Bedlington, for example, attracted a notable population from Ireland in the 1830s and 1840s.

But the discovery, in 1860, of richer iron deposits in Cleveland (an area in the far northeast of Yorkshire, bordering Co Durham) and Cumberland saw the Irish moving on.

A decade later, some 70% of nearly 900 Irish-born workers living in the Co Durham town of Consett were employed by the ironworks.

Outside London and the garrison towns of Colchester, Chatham and (from 1854) Aldershot, the south east of England attracted relatively few Irish. The same was true of other predominantly rural counties in the West Country, East Anglia and the south Midlands.

In the north, only Westmorland, a rural county with little urban development, matched the low southern rates of Irish settlement.

But even in these more rural counties, despite thier familiarity with the soil back in Ireland, they tended to settle in the county towns, rather than small villages or hamlets. Typically, Irish immigration to England meant living an urban life.

Irish immigration to England: job prospects

In non-industrial London, most Irish went into service industries. Tailoring and cobbling were two sectors that provided some skilled employment, albeit that the Irish were usually offered work in sweatshop conditions.

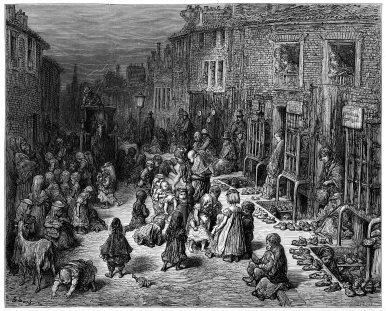

Life above the (sweat) shop in London's Covent Garden, 1871

Life above the (sweat) shop in London's Covent Garden, 1871Elsewhere, the largest concentrations were to be found in the iron and steel industries, chemical factories, shipbuilding and general labouring.

Employment in metal and shipbuilding was well paid, and the Irish were two to four times over represented numerically to what might be expected from their share of the labour force. And then there was the option of the British Army; many more Irishmen signed up than is usually appreciated.

In 1830 they accounted for more than 42% of total army personnel. It wasn't until 1891 that the percentage fell into line with Ireland's share of the UK population.

Irish immigration to England: family history records

England's main genealogy resources are in a pretty healthy state. The main ones – civil registration and census – are easy to discover and explore (usually for a fee) but more localised or specialised collections can be harder to locate and are less likely to be online. However, an increasing number of parish records, which will often provide outstanding additional information, are now being digitised.

The following list is not intended to be exhaustive but it will help any researcher unfamiliar with English family history records to get started.

No naturalisation records

There's no need to search for naturalisation resources if you're seeking details of Irish immigration to England. As Ireland was part of Britain until 1921, immigrants from Ireland had no need to be 'naturalised'.

Since Irish Independence, special arrangements have been in force; all Irish citizens having an automatic status of 'settled' in the UK.

The National Archives: the best starting point, online or offline is the National Archives at

Kew, London. Be prepared to spend time getting to grips with the website and catalogue.

Family History Societies: England has a very strong network of local family history groups. Some cover cities. Some cover counties. Join, or at least monitor, the family history society that covers your geographical area of interest. Many have a Facebook page and/or a Twitter or other social media presence.

Even if the local parish registers or more esoteric collections are not online, they will usually have fairly ready, and inexpensive, methods of obtaining information from them. Click to find a family history society in England.

Major genealogy databases: The two largest subscription or pay-per-view genealogy databases covering England are FindMyPast and Ancestry.co.uk, while MyHeritage has many of the major collections.

TheGenealogist is also an excellent and growing commercial database specialising in British records, with many collections not found elsewhere. FamilySearch and FreeBMD are the only completely free options.

Census returns: Censuses were held in 1841 and every ten years since then (except 1941). They record every man, woman and child in every household across the country on a given date (usually the end of March) and, from 1851 onwards, can be particularly useful for identifying a county or townland of origin in Ireland. The 1841 is of less value in this regard because the question asked only whether a person was born in the county of residence, or in Ireland, Scotland or Foreign Parts.

From 1851, the chance of finding a more specific place of origin starts to get better and improves with each decennial record. Nonetheless, many researchers will not find this crucial information in the census returns (in which case, you'll find some useful tips here)

Birth, marriage and death – civil registration: Civil registration started in 1837 in England. Indexes can be searched but be aware of their limitations ie births were recorded under the father's surname only until 1912; marriages were recorded under each surname separately; death certificates don't include dates of birth or names of parents until the late 20th century, etc. Start your search at FreeBMD. As its name suggests, it's completely free, and it has an online search facility for the civil registration indexes. Transcription is on-going so take a look at the Coverage Chart page.

Removal lists: The Irish were seen as a burden on the Poor Rates, through which local populations had to contribute money to support those in their communities who fell on hard times. Repatriation of 'outsiders' (whether they came from Ireland or only the next village) was a way to remove such obligations.

Use these links to view a selection of lists of people repatriated to Ireland: 1860-1862, 1867-1869 and 1875, and 1858-1875 from Liverpool.

No naturalisation records

There's no need to search for naturalisation resources if you're seeking details of Irish immigration to England. As Ireland was part of Britain until 1921, immigrants from Ireland had no need to be 'naturalised'.

Since Irish Independence, special arrangements have been in force; all Irish citizens having an automatic status of 'settled' in the UK.

Crossing the Irish Sea

Dublin to London, via Holyhead

The sea crossing from Dublin to Holyhead, on Anglesey (an island off the coast of North Wales), was originally set up as a mail route.

From Holyhead, mail was initially transferred to London by coach, a total (Dublin to London) journey time of two days. The mail contract was switched to the Liverpool-Dun Laoghaire route in 1839 (when Dun Laoghaire was known as Kingstown), leaving Anglesey to focus on building road and rail links.

It continued to offer sea crossings but journey times didn't start to shrink until the railway finally reached Anglesey in August 1848. The through sea-rail route was served by four paddle steamers (called packets).

By 1885, the London to Dublin sea-rail journey via Holyhead took 10 hours 20 minutes.

Rosslare to London, via Fishguard

A new service from Fishguard (Wales) to Rosslare in Wexford, with onward rail connection to Waterford, started up in 1906 and boasted of offering the shortest sea crossing of just 54 nautical miles. Ships took less than three hours in good weather and the steerage fare was seven shillings.

Fishguard harbour was connected by rail to Paddington Station in London. A third-class single fare between London and Waterford cost 22 shillings.

Belfast and Derry to Fleetwood

Services from Fleetwood (on England's Lancashire coast) to Belfast and Derry started running on an occasional basis in the early 19th century. A scheduled service started in 1843 and within ten years there were daily each-way sailings.

Carrying mail and cattle, as well as passengers, timetables were arranged to connect with direct trains from Leeds, Manchester and London.

Where next?

- See the Irish immigration to Britain page for a wider overview of movement across the Irish Sea.

- See Toolkit's full menu of pages about Irish emigration.