- Home ›

- Irish emigration ›

- Coffin ships

Coffin ships: death and pestilence on the Atlantic

The immigration ships that carried desperate Irish families to North America were often unseaworthy and overloaded

Quick Links/Related Pages

Coffin ships: historical context

Not all the ships that transported Irish emigrants from their homeland to Canada and America were coffin ships. The term 'coffin ship' is reserved for those that set sail during the Famine of the 1840s, often unseaworthy and uncrowded and nearly always with inadequate provisions of drinking water, food and sanitation.

This is not to say that those vessels which carried their human cargo across the Atlantic prior to the Famine would have been comfortable, hygienic or safe. After all, the history of transatlantic passage weighs heavy with disasters of all kinds, from shipwrecks in storms to starvation and dehydration in becalmed conditions.

The Ocean has always been a dangerous place.

But at the time of the Famine, when desperate and malnourished people were trying to flee poverty and starvation, the coffin ships represented the depths to which some people could stoop - whether through cynical disregard for life, pure greed or uncaring ignorance.

In 1845, potato blight seriously affected the potato harvest. For the majority of Irish people, this was catastrophic because the potato was their main, if not only, food.

In 1846, the potato crop was completely ruined and it was clear that the Government needed to act. Rather than provide food aid, Parliament introduced new taxes (which landowners would have to pay) to raise money for 'public works relief'. The latter was a two-pronged scheme. It created work for labourers so that they earn enough to feed their families with food other than potatoes. And it provided for workhouses to be built to house the absolutely destitute.

Quick Links/Related Pages

But at the time of the Famine, when desperate and malnourished people were trying to flee poverty and starvation, the coffin ships represented the depths to which some people could stoop - whether through cynical disregard for life, pure greed or uncaring ignorance.

In 1845, potato blight seriously affected the potato harvest. For the majority of Irish people, this was catastrophic because the potato was their main, if not only, food.

In 1846, the potato crop was completely ruined and it was clear that the Government needed to act. Rather than provide food aid, Parliament introduced new taxes (which landowners would have to pay) to raise money for 'public works relief'. The latter was a two-pronged scheme. It created work for labourers so that they earn enough to feed their families with food other than potatoes. And it provided for workhouses to be built to house the absolutely destitute.

The gentry were more than a little alarmed since they could see this taxation level, which they considered onerous, continuing for years. Some decided to bring a conclusion to their local problems by removing the burden altogether: by shipping their tenants to North America. They calculated that the cost of transporting each individual was considerably less than supporting that person in the workhouse for a year.

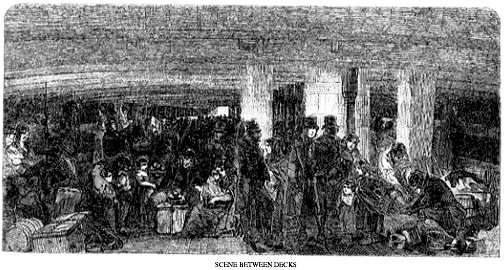

And so the first ships were commissioned and set sail, loaded with human cargo, for British North America (Canada). Many of these vessels were overloaded. Each held an average of 300 persons, some two or three times the number that would have been allowed by a port in the USA, and some were not seaworthy.

Coffin ships: Setting sail in 1846/7

Up to the middle 1840s, ships from Northern Europe sailed only in spring and summer to ensure they avoided ice and bad weather on their transatlantic voyage.

But in 1846, the most severe winter in living memory, immigration ships continued to sail from Ireland. Most headed southwest, to US ports. Alarmed at the level of destitution and illness arriving with these vessels, the US Congress quickly passed two new Passenger Acts in order to make the voyage even more expensive. That following March, the minimum fare to New York rose to £7, an amount way beyond the majority of families facing starvation in Ireland. Even so, all tickets had been sold by the middle of April.

That year, some 85,000 sailed directly from ports in the south and west, principally Cork/Queenstown and Limerick. Another 11,000 departed from Sligo while 9,000 left from Dublin and 4,000 crossed the Irish Sea to catch a ship from the English port of Liverpool.

The numbers who sailed from tiny fishing harbours such as Baltimore, Killala and Tralee are not known, but we can be confident that the passenger acts were not being enforced and conditions for their passengers were horrendous.

In time, these boats became known as 'coffin ships' because, as the Irish Times described, their passengers "were only flying from one form of death". While they may have left starvation behind, many of these passengers were already in extremely bad health after a year or more of inadequate nutrition and exposure to illness.

With their physical state already desperate, the last thing they needed was to be crammed into overcrowded, insanitary conditions with hundreds of others.

Just one case of typhus, which was rampant among the poor at this time, could spread like wildfire in the conditions on the coffin ships, and many were to die before, or shortly after, reaching the other side of the Atlantic. Others drowned when their ships were overwhelmed by ocean storms or fell upon rocks.

The ships that survived the Atlantic crossing arrived at the quarantine station of Grosse Isle, the Canadian immigration point and depot set up in the Gulf of St Lawrence (Ontario) in 1832, to contain diseased immigrants to British North America. Statistics for just one month - July 1847 - indicate the horrors that were being indured. Ten vessels arrived that month; of the 4,427 Irish immigrants that had started their journeys (all had departed from either Cork or Liverpool), 804 had died on the passage while 847 were sick on arrival.

By the end of 1847, the awful toll could be calculated from the 441 immigration ships that had made the crossing. Of 98,105 passengers (of whom 60,000 were Irish), 5293 died at sea, 8072 died at Grosse Isle and Quebec, 7,000 in and above Montreal. In total, then, at least 20,365 people perished (the numbers of those that died further along in their journey from illnesses contracted on the coffin ships cannot be ascertained).

The Ocean Plague – A diary of a coffin ship voyage

This book, subtitled 'A voyage to Quebec on an Irish Emigrant vessel', was written by Robert Whyte who sailed from Liverpool on 30 May 1847 as a cabin (ie first class) passenger. It delivers a graphic and uncomfortable account of the hardships endured by over 100 Irish passengers, most of them from County Meath and travelling at the expense of their landlord.

The Famine Memorial at Murrisk, Co Mayo.

The Famine Memorial at Murrisk, Co Mayo.The book is highly recommended to those who wish to truly understand what their Irish ancestors endured when they left Ireland on one of the coffin ships during the famine. The full text is available free on Google Books. Here are two extracts:

- Whyte describes the symptoms of what the emigrants called 'ship fever':"The first [symptom] is usually a reeling in the head, followed by a swelling pain, as if the head were going to burst. Next came excruciating pains in the bones, and then a swelling of the limbs, commencing with the feet, in some cases ascending the body and again descending before it reached the head, stopping at the throat. The period of each stage varied in different patients, some of whom were covered with yellow, watery pimples, and other with red and purple spots, that turned to putrid sores."

- Whyte recalls a passenger bewailing the folly that had tempted him to take his family on the voyage: "We thought we couldn't be worse off than we war; but now to our sorrow we knowt he differ; for sure supposin we were dyin of starvation, or if the sickness overtuk us. We had a chance of a doctor, and if he could do no good for our bodies, sure the priest could for our souls; and then we'd be buried wid our own people; in the ould churchyard, with the green sod over us; instead of dying like rotten sheep thrown into a pit, and the minit the breath is out of our bodies, flung into the sea to be eaten up by them horrid sharks."

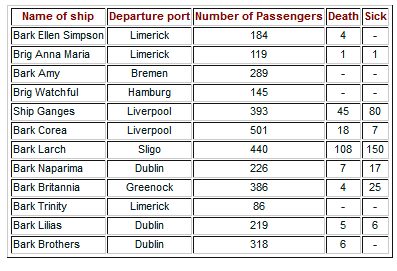

Ships in Grosse Isle, 9 August 1847

The table here shows the vessels at the Canadian immigration point and quarantine station of Grosse Isle, on 9 August 1847. The coffin ships from Ireland are easy enough to identify.

Compare them with the ships from Hamburg and Bremen whose emigrants reportedly arrived 'healthy, robust and cheerful'.

These statistics provide a snap shot of just one day in that dreadful year when so many coffin ships sailed to North America.

Other vessels for which records survive include the Sir Henry Pottinger from Cork which sailed with 399, lost 98 during the voyage and arrived with 112 sick.

The Bark Wellington sailed from Liverpool with 435, buried 26 at sea and arrived with 30 sick. The Bark Sir Robert Peel sailed from the same port with 458, buried 24 en route and arrived with 12 sick.

Montreal's mass graves

In the St Lawrence River, some 30 miles east of Quebec City, the quarantine station at Grosse Isle was soon overwhelmed with the numbers of sick passengers crawling or carried off the coffin ships. It couldn't treat those that were ill, let alone provide for those that were not. So those that appeared healthy remained onboard their immigration ships and were simply waved on to Montreal.

Unfortunately, many had already caught typhus the fever that ran rampant on their overcrowded and dirty vessels and they were to become ill further upriver. Soon, it was Montreal that was overwhelmed with the dead and dying.

Ten years after the year of the coffin ships, workers building the city's Victoria Bridge unearthed a mass grave containing the remains of about 6000 Irish immigrants. A 27-tonne granite boulder marks the spot beside the bridge's entrance where an annual ceremony remembers those who died escaping poverty and hunger.