|

|

|

From flax plant to Irish LinenTransforming the flax plant gave work to all the family

Traditionally, the process involved many members of a family. Men were usually responsible for seeding while women took charge of weeding as the plants grew. Keeping weeds to a minimum not only encouraged vigorous growth, it also meant the stem was more likely to grow upright.

At about one metre in height, the plant was ready for harvest, an operation that usually involved all adults and older children. When they had dried, the seeds were removed and saved either for next year's planting, or to make linseed oil or cattle feed. (See the left-hand column for details of how this remarkable plant is used as an important component in many day-to-day products.)

Retting5 steps of yarn production After drying, the flax plant is transformed into yarn in five stages: (l-r) Pulled flax; Retted flax; Scutched flax; Hackled flax; Spun flax (yarn). Click image for enlarged view. For our rural Irish ancestors, retting was an unmistakeable feature of life because the stench of the decomposing plants hung heavily over the countryside. Smelly though it was, retting helped to separate the valuable fibres from the core of the stem. After ten days, the retted flax could be removed from the pond. It was hard and unpleasant work lifting the heavy, sodden, stinking mess from the water.

Scutching & HacklingAfter a few weeks drying off the rotting flax plants in fields, the next steps of the process began. Scutching was an unhealthily dusty job and was usually, but not always, performed by men as it required quite a bit of stamina. It involved beating the stems with a wooden mallet or blade to separate and clean the flax fibres, resulting in a tangled bunch of fine fibres.These were then straightened by a hackler using combs of decreasing fineness. Hackling made the fibres soft and ready for spinning into a continuous thread: yarn.

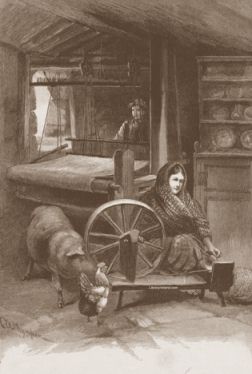

Spinning Both sexes could be involved in hackling but it was always women who spun the fibre into yarn.

This is where the term 'spinster' originated and why it can only be applied to a woman.

Both sexes could be involved in hackling but it was always women who spun the fibre into yarn.

This is where the term 'spinster' originated and why it can only be applied to a woman.

Spinning was done on a low Irish wheel which was kept in motion by a foot treadle and resulted in bobbins of yarn which were then boiled in soapy water and dried. Even very young children played their part in the process by winding yarn onto pirns or bobbins. From the spindle, the yarn was transferred to a loom to be woven into a cloth which, in its natural state, was a brownish colour. WeavingIn the days before industrialisation of the linen market, many households had two or more looms and weaving was done by men. When the mills and factories took over the industry in 1830s, it was women who began to take charge of the looms, even those who were homeworkers under the so-called 'putting out' system. The main reason was that mill spun yarn was widely available and was easier to weave.The introduction of power looms spelt the beginning of the end for the domestic, cottage-based, industry. In 1850 there were fewer than 60 of them in Ireland but within 25 years, there were more than 17,000. Even so, hand loom weaving of the very finest Irish linen fabric continued in workshops in the Linen Homeslands of Ulster for another 50 years. BleachingTraditional bleaching methods included boiling the cloth in a solution of water and ashes, seaweed or fermented bran. The cloth was then rinsed and spread over an area of grass (bleach greens) to dry in the sun. Having aired, it was steeped in buttermilk, rinsed and spread out again. This process was repeated many times.All this rinsing in Irelands soft water was said to be the secret ingredient that made Irish Linen superior. BeetlingBeetling involved the pounding of the cloth with mechanised mallets to close up the weave. It was the final process in the transformation of the flax plant into beautiful cloth. This action is what gives Irish linen its dense sheen.

|

| ||

|

|

|||

|

| Home Page | Disclaimer | Contact |Sitemap|Privacy Policy|

By Claire Santry, Copyright©

2008-2020 Irish-Genealogy-Toolkit.com. Dedicated to helping YOU discover your Irish Heritage.

|

|||

Care had to be taken in pulling the flax from the ground so that every inch of the stem would be retained.

These stems were bundled together into sheaves (called beets) before being carried in carts to fallow fields where women and girls would spread them into stacks called stooks and leave them to dry in the sun.

Care had to be taken in pulling the flax from the ground so that every inch of the stem would be retained.

These stems were bundled together into sheaves (called beets) before being carried in carts to fallow fields where women and girls would spread them into stacks called stooks and leave them to dry in the sun.