- Home ›

- Irish emigration - main page ›

- Immigration to Britain

Irish immigration to Britain

Irish immigration to Britain - emigration from Ireland to England, Scotland or Wales - was nothing new even before the mass exodus of the Famine years (1845-1849). Up to the time of that crisis, Britain had always been the principal destination of Irish migrants, whether their movement was temporary eg. for seasonal work, or permanent.

If you have Irish ancestors who crossed the Irish Sea, you'll want to know why and how they made the journey. This page will provide an overview. There are also separate pages looking in more detail at Irish immigration to Britain's three constituent countries of England, Scotland and Wales, and where to find genealogy records. See the Related Pages box in the right-hand column for links to those pages.

If you have Irish ancestors who crossed the Irish Sea, you'll want to know why and how they made the journey. This page will provide an overview. There are also separate pages looking in more detail at Irish immigration to Britain's three constituent countries of England, Scotland and Wales, and where to find genealogy records. See the Related Pages box below for links to those pages.

There's one crucial feature of Irish immigration to Britain that you should be aware of: there are no passenger lists of people who crossed the Irish Sea by ship.

Unlike those Irish emigrants who set sail for Canada, the USA, Australia and New Zealand, passengers leaving Ireland on ships to England, Scotland and Wales were not counted or recorded on embarkation nor were they counted or recorded on disembarkation.

They were, to all intents and purposes, internal migrants.

This is because Ireland was a part of Britain until 1922; just as today's travellers don't have to show a passport when they cross the Severn Bridge between England and Wales or when they're on a train journey from Newcastle to Edinburgh, unrestricted travel within Britain was the norm. There was no formal monitoring of movement.

Reasons

for Irish immigration to Britain

Until the Famine of the 1840s, Britain was the number one destination for Irish migrants. In the three decades that followed, transatlantic migration took over. Thereafter, the pattern of migration followed the peaks and troughs of economic activity in the USA and Britain.

No passenger lists

The complete lack of ship passenger lists can present a major problem for genealogy researchers who are trying to work back to Ireland from a family line that settled in England, Scotland or Wales.

Most genealogy records in Britain won't provide specific details of where in Ireland the immigrant ancestor came from. They'll just record 'Ireland'.

In the absence of passenger records detailing a last place of residence, the researcher is in difficulty because to make progress with Irish genealogy records it's essential to know a geographical place of origin.

This issue is discussed in more depth in the Irish immigration to England/ Scotland pages.

(See Related Pages.)

The reason for mass Irish immigration to Britain or anywhere else on the planet during the famine years is obvious enough but at other times the picture is more complex.

There were a number of push and pull factors. Of the former, inequality at home and the drudgery of a marginal existence were sufficient motivation to up sticks and away.

Pull factors included the prospect of comparatively well-paid employment in Britain or America's industrialised urban centres, letters home from family members who had already emigrated, the propaganda of shipping countries telling of the prosperous and beautiful life that could be had abroad, and, for those who went to the USA, independence from British rule.

No passenger lists

The complete lack of ship passenger lists can present a major problem for genealogy researchers who are trying to work back to Ireland from a family line that settled in England, Scotland or Wales.

Most genealogy records in Britain won't provide specific details of where in Ireland the immigrant ancestor came from. They'll just record 'Ireland'.

In the absence of passenger records detailing a last place of residence, the researcher is in difficulty because to make progress with Irish genealogy records it's essential to know a geographical place of origin.

This issue is discussed in more depth in the Irish immigration to England/ Scotland pages.

(See Related Pages.)

The exodus started with the Presbyterian Ulster Scots who headed for America in the late 17th century (see the main Irish emigration page). Those with resources, aspirations and motivation followed some to Britain, some to North America.

But there was one critically important pull factor behind Irish immigration to Britain specifically: proximity.

Seasonal migration across the Irish Sea, mainly for casual labour, had a long history and would not have been feasible or worthwhile if the journey were particularly arduous, long or expensive.

The psychological leap from seasonal work to semi-permanent emigration is not so great, and it's likely that many who came to Britain expected to return to their homeland one day. While permanent settlement may not have been intended, it was the reality for most.

The path of Irish immigration to Britain

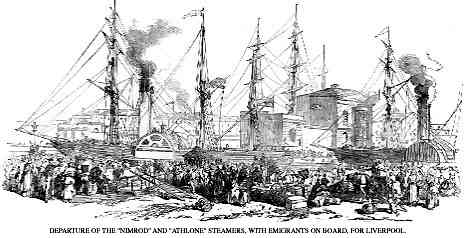

Irish immigration to Britain took off in 1818 with the first steam packet service (the Rob Roy) linking Belfast to Glasgow. Within a decade, ships were also ferrying passengers from Dublin and Cork, mainly to Liverpool for onward travel to North America.

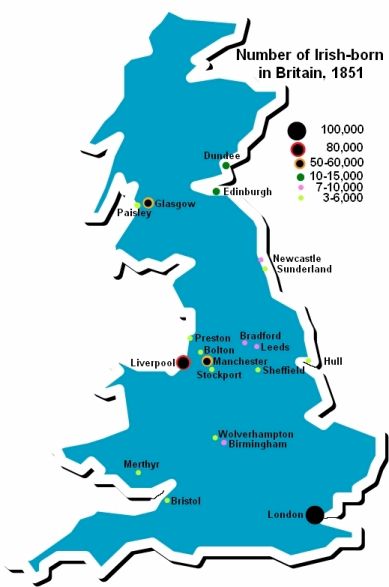

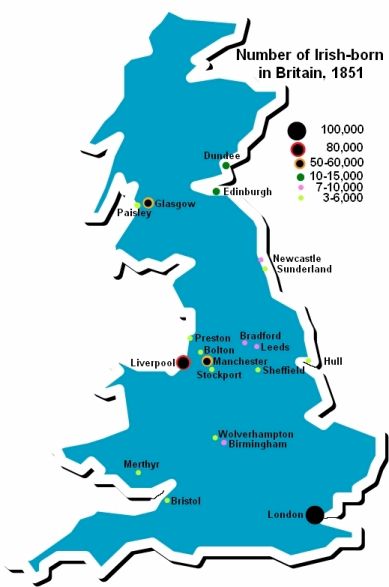

Having made the decision to leave, the emigrant's choice of settlement in Britain was determined by three factors: proximity to Ireland, ease of sea passage, and the availability of regular work. As such, the main magnets were ports of arrival, towns on the western side of Britain, and industrialised urban centres further inland.

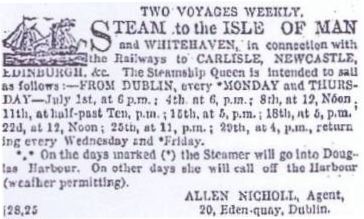

Newspaper advert, June 1861

Newspaper advert, June 1861The most important factor in determining final settlement was ease of transport across the sea.

Someone in Tyrone or Derry, dreaming of life after emigration, was really thinking about life and work in Barrow in Furness, Cumbria or one of the towns near the west coast of Scotland. It's unlikely they were thinking of South Wales or Bristol.

Similarly, would-be emigrants in Munster were hoping for new lives in Wales, Cornwall or London; Scotland was not on their horizon.

The main

route patterns for Irish immigration to Britain

In general,

- Emigrants from Ulster settled in Scotland

- Emigrants from Connacht and the central strip of Ireland travelled via Dublin to Liverpool

- Emigrants from Munster and

other southerly or western areas of Ireland sailed to South Wales, London

or the English south coast.

As with all generalisations, this overview overlooks the thousands who found a non-typical route. In 1881, a quarter of the Irish-born population of Newcastle-upon-Tyne came from Ulster. They had probably travelled via Barrow-in-Furness or Whitehaven, both of which were important ports for ships from Ulster, especially for passengers from counties Tyrone, Antrim and Down, and had good transport links across the Pennines, to London and to Edinburgh.

But nearly half the Irish-born population of the town came from western Connacht. They would have travelled from Dublin or, in smaller numbers, from Belfast.

Also flying in the face of the accepted generalisation is the number of immigrants in Yorkshire who started out from Munster.

Top 10 centres of Irish settlement:

(Irish-born as % of total population)

|

1851 |

% |

1871 |

% |

|

Liverpool |

22.3 |

Dumbarton |

17.7 |

|

Dundee |

18.9 |

Greenock |

16.6 |

|

Glasgow |

18.2 |

Liverpool |

15.6 |

|

Cardiff |

16.2 |

Glasgow |

14.3 |

|

Manchester |

13.1 |

Airdrie |

14.2 |

|

Paisley |

12.7 |

Dundee |

11.9 |

|

Kilmarnock |

12.1 |

Paisley |

9.8 |

|

Newport |

10.7 |

Middlesboro' |

9.2 |

|

Stockport |

10.6 |

Manchester |

9.0 |

|

Bradford |

8.9 |

Hamilton |

8.6 |

Top 10 centres of Irish settlement:

(Irish-born as % of total population)

|

1851 |

% |

|

1871 |

% |

|

Liverpool |

22.3 |

|

Dumbarton |

17.7 |

|

Dundee |

18.9 |

Greenock |

16.6 | |

|

Glasgow |

18.2 |

Liverpool |

15.6 | |

|

Cardiff |

16.2 |

Glasgow |

14.3 | |

|

Manchester |

13.1 |

Airdrie |

14.2 | |

|

Paisley |

12.7 |

Dundee |

11.9 | |

|

Kilmarnock |

12.1 |

Paisley |

9.8 | |

|

Newport |

10.7 |

Middlesboro' |

9.2 | |

|

Stockport |

10.6 |

Manchester |

9.0 | |

|

Bradford |

8.9 |

Hamilton |

8.6 |

In general,

- Emigrants from Ulster settled in Scotland

- Emigrants from Connacht and the central strip of Ireland travelled via Dublin to Liverpool

- Emigrants from Munster and other southerly or western areas of Ireland sailed to South Wales, London or the English south coast.

As with all generalisations, this overview overlooks the thousands who found a non-typical route. In 1881, a quarter of the Irish-born population of Newcastle-upon-Tyne came from Ulster. They had probably travelled via Barrow-in-Furness or Whitehaven, both of which were important ports for ships from Ulster, especially for passengers from counties Tyrone, Antrim and Down, and had good transport links across the Pennines, to London and to Edinburgh.

But nearly half the Irish-born population of the town came from western Connacht. They would have travelled from Dublin or, in smaller numbers, from Belfast.

Also flying in the face of the accepted generalisation is the number of immigrants in Yorkshire who started out from Munster.

Irish immigration to Britain – finding work

Both before and after the Famine of the 1840s, Irish immigration to Britain followed the pattern of industrialisation.

Although there were periods and areas of resistence to their arrival, the Irish found it relatively easy to find work mainly because they were willing to take on gruelling work, often in harsh environments. While the work was hard and low skilled, it was not necessarily poorly paid. It is true, however, that many of the dirtiest, least healthy and most dangerous jobs seemed to recruit a disproportionate number of Irish.

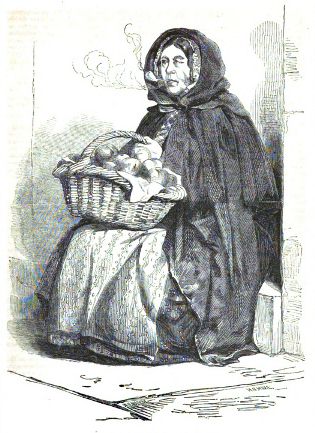

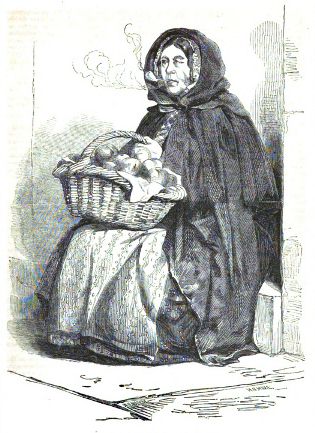

The Irish Street-Seller,from Henry Mayhew's 'London Labour and the London Poor', 1864

The Irish Street-Seller,from Henry Mayhew's 'London Labour and the London Poor', 1864Famously, the Irish came to dominate the construction industry in the Victorian era. While many found skilled work as masons, carpenters and bricklayers, the vast majority were unskilled labourers, putting their back into work that was neither socially marginalising nor poorly paid. (See The Irish Navvy in the right hand column.)

The Irish Street-Seller,from Henry Mayhew's 'London Labour and the London Poor', 1864

The Irish Street-Seller,from Henry Mayhew's 'London Labour and the London Poor', 1864Famously, the Irish came to dominate the construction industry in the Victorian era. While many found skilled work as masons, carpenters and bricklayers, the vast majority were unskilled labourers, putting their back into work that was neither socially marginalising nor poorly paid. (See The Irish Navvy below.)

There was also a significant number of Irish in the service sector. Street selling or hawking made up the largest category of work for Irish women in Scotland even as late as 1911 when it accounted for nearly 9% of working females.

Working from barrows, hand carts or baskets, they sold flowers, fruit, heather brushes, matches and other small items.

The Irish also ran lodging houses. These were often in the poorest areas of town and provided dirt-cheap accommodation for their countrymen as Irish immigration to Britain continued unabated throughout the 19th century.

They also ran pubs, of a kind that could be combined with a day job. In Cumbria, for example, many Irish-born men are recorded in the censuses with dual occupations such as 'iron ore miner and beer seller'.

Irish immigration to Britain - summary

The nature and pattern of Irish immigration to Britain differed in several respects to the migrations to North America and Australasia:

- It didn't have quite the same quality of permanence. It was a short distance and there were long-standing cultural, economic, political and social links between the two neighbours.

- Irish immigration to Britain had been going on since the Middle Ages so there were already several Irish communities in some large towns including London, Bristol, Canterbury and Norwich, and in garrison towns such as York.

- Many Irish soldiers in the British army took up permanent residence in Britain following their discharge from military duties.

- A tradition of seasonal migration from Ireland to Britain existed. Smallholders, especially from Connacht and Munster, would regularly seek casual employment. Much of this work was agricultural, to help with harvesting, but casual labourers were also required from time to time in the docks and mines and on large civil engineering projects.

- A significant proportion of Irish who initially settled in Britain after the Famine eventually set sail for the USA or Australia. This is known as 'step migration'.

The nature and pattern of Irish immigration to Britain differed in several respects to the migrations to North America and Australasia:

* It didn't have quite the same quality of permanence. It was a short distance and there were long-standing cultural, economic, political and social links between the two neighbours.

* Irish immigration to Britain had been going on since the Middle Ages so there were already several Irish communities in some large towns including London, Bristol, Canterbury and Norwich, and in garrison towns such as York.

* Many Irish soldiers in the British army took up permanent residence in Britain following their discharge from military duties.

* A tradition of seasonal migration from Ireland to Britain existed. Smallholders, especially from Connacht and Munster, would regularly seek casual employment. Much of this work was agricultural, to help with harvesting, but casual labourers were also required from time to time in the docks and mines and on large civil engineering projects.

* A significant proportion of Irish who initially settled in Britain after the Famine eventually set sail for the USA or Australia. This is known as 'step migration'.

Because Ireland was for so many years either a part of Britain or subject to it, many historical records relating to the island and Irish people are held in the UK's National Archives in Kew, West London.

Irish-born populations of

England, Scotland & Wales, 1841-1921

1841 - 415,725

1851 - 727,326

1861 - 805,717

1871 - 774,310

1881 - 781,119

1891 - 653,122

1901 - 631,629

1911 - 550,040

1921 - 523,767

The Irish navvy

The elite of the labourers working in Britain were the Irish 'navvies'.

The first navvies were the men who had built the 3400 miles of canal that make up the British inland navigation system between 1745 and 1830. The term, which is still readily recognised today, later came to be used for any labourer working on large-scale civil engineering project.

By the mid-1800s, at the height of Britain's railway construction boom, some 250,000 navvies were employed, most of them professional and seasoned workers. They had mastered the 'graft', a drain-digging spade which became the symbol of their trade, and joined a largely itinerant workforce that, until towards the end of the century, lived in huts beside each major project and moved on when it was finished. Conditions within the huts were not pleasant; cholera, dysentery and typhus were common, as were hard drinking and violence. .

As the 19th century moved on, navvies became increasingly recognised for their expertise, strength and stamina. A good navvy could shift 20 tonnes of earth a day but his skills went further than digging. The job required expertise in quarrying, brickmaking, ,joinery, ironwork, laying rails and pipes, and building tunnels, bridges and locks.

In return for their hard graft, navvies demanded high wages. In 1845, the daily rate was nearly four shillings – about double that earned by an agricultural labourer.