- Home ›

- Genealogy & DNA Testing ›

- DNA facts

DNA facts for beginners

Why is DNA important? What is

DNA? What is a mutation?

This DNA facts page is aimed at the layman or laywoman who wants to get a basic understanding of how and why DNA testing may be worth considering as part of your family history research.

Although I have taken tests myself and arranged for my male siblings to take tests, my knowledge is strictly non-academic, and I do not pretend to be a geneticist or DNA expert. If you already know a lot about DNA and/or want very detailed or specialised information about it, you would be better served seeking out sites written by specialist geneticists.

Article by Claire Santry FIGRS. Last reviewed and updated on 6 November 2023.

What do the letters DNA stand for?

They are the accepted abbreviation for DeoxyriboNucleic Acid.

What is DNA?

A human DNA molecule is made up of two strands wrapped around each other like a twisted ladder (this is where the term 'double-helix' originates). The rungs of this 'ladder' consist of chemicals containing nitrogen, and these rungs are called Bases. There are four bases:

- Adenine (A)

- Cytosine (C)

- Guanine (G)

- Thymine (T)

Human DNA has about three billion of these, and the sequence in which they appear along the strand determines what characteristics they deliver to a person. So, for example, whether you have blue, brown or green eyes depends (largely) on whether your sequence at the crucial point is AGGCT, ATTCG, or another combination.

More than 99% of the bases are the same in every individual person. It is only the small variations that makes each ofus unique.

Anything from one thousand to one million bases join together to make a single DNA sequence a gene. Some 20,000-25,000 genes create the human body.

Which types of DNA test are used for genealogy research?

While

there are many different types of DNA test, there are really only three tests which

are used for genealogy research: the Y-chromosone (Y-DNA) test, the

mitochondrial (mtDNA) test and the relatively new - and very popular - autosomal (atDNA) test. The Y-DNA and autosomal tests have the most interest or clear

relevance to genealogy.

Find out

more about these three main types of DNA test.

When did DNA testing for ancestry start?

The first commercial DNA tests for genealogy purposes became available just before the close of the 20th century. Since then, prices have dropped considerably and more types of DNA test have come on stream.

In 2009 I read a statistic that nearly one million people had paid to have a DNA test either to help or supplement their traditional genealogy research or to uncover their deep ancestral origins. In the intervening years, many more businesses have set up to offer a full range of DNA testing options, and some of the biggest commercial suppliers of genealogical databases have introduced their own genetic services, typically offering autosomal testing.

In April 2018, nearly six years after launching its DNA autosomal test, Ancestry reported that its database held dna tests from almost 10 million individuals. MyHeritage DNA, which launched only in November 2016, had more than 1 million at the beginning of 2018. I don't know how many tests have been carried out by FamilyTreeDNA, a company with a much wider range of products available, and I know next to nothing about 23 and Me, which seems better recognised in the USA than in Ireland and Europe.

DNA facts: Y-chromosone (Y-DNA) tests

The Y-DNA test looks at markers on the Y-chromosone which is passed down, virtually unchanged, from father to son (women don't have a y-chromosone).

Over time, mutations occur and these show up on the markers. Scientists can identify the mutations on these markers and, by comparing results, identify individuals who share the same marker patterns. The more matching markers two individuals have, the more closely they are related.

Costs for a Y-DNA test vary considerably depending on how many markers you choose to be tested. Within surname projects, a test of 37 or 43 markers is usually required, but there are also tests for 67 markers which can be useful for complicated situations such as adoption or illegitimacy.

More Y-DNA facts, including the so-called paternity DNA test, and their genealogical role.

DNA facts: Mitocondrial DNA (mtDNA) testing

MtDNA is the accepted abbreviation for mitochondrial DNA, which is passed from a woman to her children. Men cannot pass on mtDNA.

Mitochondrial DNA is not found in the cell but outside it.

An mtDNA test tracks your maternal line only. As with the Y-DNA test, scientists are looking out for mutations on markers of the mtDNA matter. But, compared with Y-chromosone changes, mtDNA mutations occured at a much slower rate down the centuries so this test is of rather less immediate use genealogically than the Y-DNA test. Mitochondrial DNA testing can provide an insight to an individual's 'deep ancestry', ie to where your distant ancestors might be from, geographically. Mitochondrial DNA facts and genealogical value.

DNA facts: Autosomal (at-DNA) testing

'Traditionally', only two dna tests were used by family historians: the Y-chromosome (Y-DNA) tests looked for surname matches down the direct paternal line, while mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) tests explored genealogical matches down the direct maternal line.

It was not until about 2010 that atDNA tests arrived on the scene, examining the 22 autosomal chromosomes on all ancestral lines and locating shared segments of dna between the tests of individuals. The test then predicts relationships based on the number and length of shared dna segments. In practice, autosomal testing works best in finding familial connections up to fourth and fifth cousins. It has also proved extremely popular among people wanting to know their ethnic heritage.

DNA facts: Mutations

Don't be alarmed! Mutations in your genetic profile doesn't mean you are descended from mutants!

Although DNA passes down the generations, it doesn't stay exactly the same forever. Sooner or later it changes. These changes are called mutations, and they're harmless.

Over time, different groups and families create their own identifiable mutations. These groups can also become associated with the geographical areas they moved to. These mutations don't happen frequently but over millenia they have made up a huge portfolio of variables.

Only 40-odd major groups of people with similar DNA (haplogroups) have been identified.

DNA facts: Haplogroups

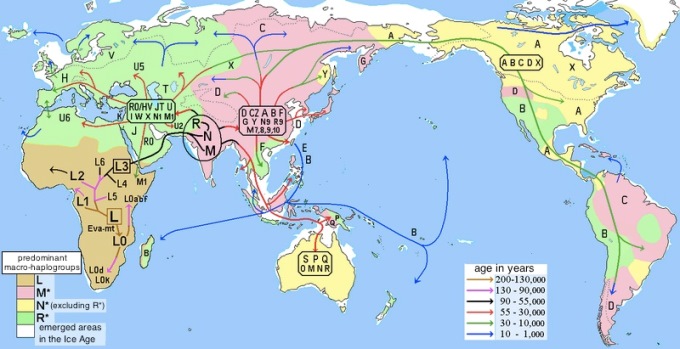

Haplogroups exist for both Y-DNA and mtDNA, but I'll use the latter to illustrate the term. The theory is that the woman from whom we are all descended lived in Africa some 100,000+ years ago. She's been named Eve, for simplicity's sake.

About 60,000 years ago, Eve's descendents spread across Africa and some then headed northwards. They continued to move on, some heading for South Asia and Australasia, others to East Asia. About 15,000 years ago some of their descendents started to enter Europe while others crossed a land bridge between Siberia to North America.

Every 20,000 years or so the mtDNA of Eve's descendents mutated (ie changed) and these mutations have come to be associated with groups (haplogroups) of people at specific points along this journey.

Each haplogroup has been identified by letters of the alphabet (A-R for Y-DNA, A-Z for mtDNA), and can be further refined into sub-branches known as 'sub-clades' ie U5b1.

People who share their haplogroup with the original Eve, for example, belong to haplogroup L1 which is found in people from west and central sub-Saharan Africa. This group never strayed from this region. Some of the descendents of those people (haplogroup H), meanwhile, made the long journey into chilly western Europe. About 40%+ of modern Europeans share this haplogroup.

Haplogroups are about 'distant ancestry'. Knowing which haplogroup you belong to will not help you to add names and dates to your family tree chart, or tell you how or where your ancestors were living before written genealogy resources were created. If you meet someone who shares your haplogroup, it does not mean you are closely related. It means your ancestors followed a similar migration path.

An interesting timeline showing the way haplogroups have divided and subdivided.

DNA facts: Surname Projects

Although there are exceptions, across most societies men have inherited their father's surname. They also inherit their father's Y-DNA. This makes Y-DNA and surnames natural partners, genealogically.

The aim, then, of a surname project is for men with the same surname to take y-DNA tests and then gather together all the results into a database. Men who match with others have a common ancester. The number of identical 'markers' on the test results will determine whether that common ancestor is distant. If recent, the two people may be able to extend their genealogy research by swopping trees and other information.

Surname projects are set up by an administrator with a laboratory/DNA-testing company. They come in all shapes and sizes and while most study the surname on a worldwide basis, some focus on a specific geographical region. As the database grows, the project becomes increasingly useful.

Some surname projects offer discounted test prices.

More about DNA Surname projects.

Find out more

Click to view the full menu of pages about Genealogy tests & DNA facts.

View Debbie Kennett's video 'DNA Testing for Beginners'. This lecture was presented at the Genetic Genealogy Ireland 'Who are the Irish' conference in 2015 and provides a thorough grounding in DNA for all family historians (whether Irish or not). It's getting old, but is still, in my opinion, the best 'beginners' tutorial.